Inside "Star Wars: The Force Awakens"

/By Maia Jasper White

I’m not much of a Star Wars fan. I’ve only recently — and partially — seen Episodes 4 and 5. (Partially, because I fell asleep during both viewings.) This has led people of all ages to inquire about my legitimacy as a citizen of Planet Earth.

For what it’s worth, I’m likewise ignorant of many other pop cultural tropes. Never ask me the lyrics to, well, any ubiquitous song. Somehow, I’m missing a chip necessary for the absorption of contemporary zeitgeist. While my high school peer group was committing the Top 40 to memory via osmosis, I was shedding tears over Debussy’s String Quartet. Many a friend’s head has shaken in dismay at my limited pop cultural knowledge. Feeling a bit out-of-the-loop is the price I’ve paid for a lifelong attraction to the (relatively) esoteric and arcane.

While this is not something I’m proud of, neither is it something I long to change. The case of cultural FOMO with which I am afflicted is mild. It has yet to inspire me to recalibrate my natural tastes.

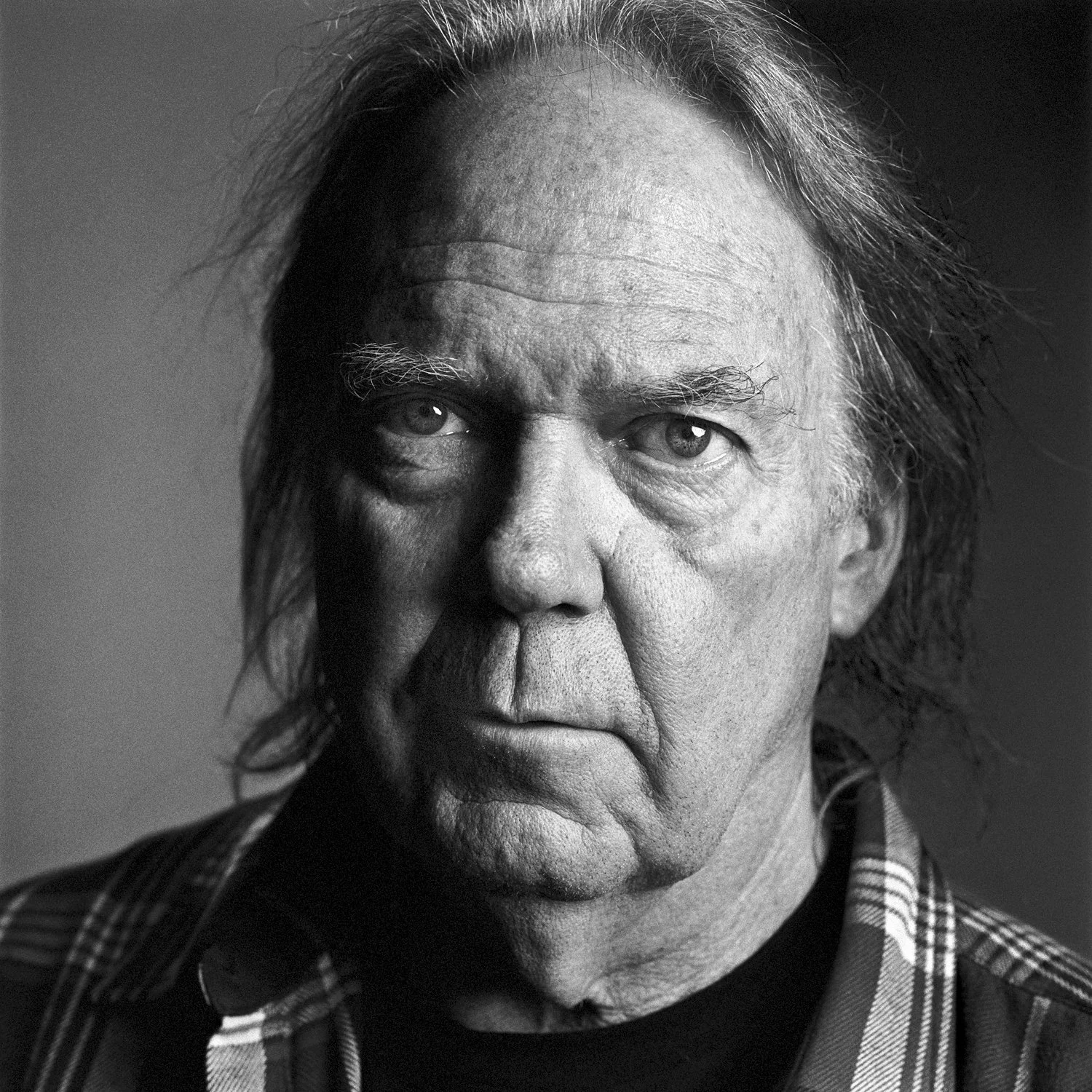

Instead, I’d like to think my obliviousness endears me to others. When called for a Neil Young session a year or so ago, I asked my husband if the singer in question “was famous.” His response: “that would be the rock equivalent of asking if Jascha Heifetz is famous.” (Duly noted.)

Who's this guy?

Imagine, then, my strange good fortune in playing a tiny part in the latest installment of Star Wars.

Alex Ross wrote a thoughtful piece on John Williams and “The Force Awakens.” In this post, I’ll share some of my memories and experiences recording the score.

Prior to “The Force Awakens,” I’d played my fair share of Williams’ music in concert. The intricacy and integrity of his writing always demands a certain level of quality from your playing. This demand is a hallmark of, well… good music.

Alex Ross writes:

After “Star Wars,” [Williams] became a sound, a brand. The diversity and occasional daring of the composer’s earlier work—I’m thinking not only of “Close Encounters” but also of Robert Altman’s “Images” and “The Long Goodbye” and of Brian De Palma’s “The Fury”—subsided over time. Williams invariably achieves a level of craftsmanship that no other living Hollywood composer can match; his fundamental skill is equally evident in his sizable catalogue of concert-hall scores. Yet he’s been boxed in by the billions that his music has helped to earn. He has become integral to a populist economy on which thousands of careers depend.

Because everything about the movie was kept under lock and key, they put out a fake name (“AVCO”) for the call. But everyone knew what it was. And not just because the main title on the stand gave it away.

The LA studio musician scene was abuzz with excitement. Scoring the movie in LA, by union musicians, was a significant and timely coup. Significant, because every prior Star Wars films had been recorded in London. Timely, because the LA studio community has, for years now, been in a heated debate. The topic: how can we compete with outsourcing, and the threat to our livelihood it poses?

For many reasons, everyone brought their A Game for these sessions. People dressed sharply, arrived even earlier than usual, and came prepared. (Session music isn’t typically sent to the musicians ahead of time; this was.) Eating and drinking on the stand were prohibited. Suffice it to say that these were Sudoku-free sessions. Chit-chat, too, was at a minimum.

The quiet excitement in the room was palpable. So was deep respect for John Williams. Applause and smiles greeted him every day, and thanked him at the end. The room hung on his every word, whether he was telling a story or delivering musical notes. His comments revealed an understanding that few other living film composers match.

As proud last chair second violin, I sat in front of the french horn section. At one point during Kylo Ren’s theme, Williams asked them to tongue something differently. I can’t remember what, exactly, he wanted. His knowledge of the instruments of the orchestra is what came through — with a depth and class that is rare.

Williams agrees: Jessica's OBoe playing is just as lovely as she is. (You're cute too, Ben.)

The players delivered accordingly. Everyone sounded fantastic. I was especially proud of two close friends: Jessica Pearlman Fields and Ben Smolen. Another good friend, Jenni Olson, wrote her own blog post about her experiences playing flute on the score. They killed everything they played, and left a strong impression on everyone in the room. Watching friends shine never grows stale.

Williams himself kept remarking on the caliber of the horn section. They sounded so fantastic, he said, that he was certain he’d be the envy of every film composer around. I loved sitting closest to the beast that is Andrew Bain. Hearing him steel himself before each entrance was inspiring, as was his consistent and impeccable delivery.

And I’m proud to share that some of the horn players got something out of sitting near me.

Let me explain.

Playing in the studios can be, oh, a bit nerve-wracking. Once the red light comes on, no audible flaws are permitted. Clearing your throat alone can ruin a take. To get out my juju in a silent, non-disruptive way, I like to play with tangle toys. During a break, one of the horn players approached me. He told me he drives his colleagues nuts by bouncing his knee up and down in rapid-fire succession. He wanted to know about my fidget toy. He and another horn player are now converts. (Yes, this is me taking partial credit for how good the horns sounded. Anytime, John… anytime.)

Kevin struggling to contain himself. background: JJ Abrams & williams

Kevin beamed — grimaced, more like it — while playing what I later learned was the Millenium Falcon theme. (“I’m geeking out so hard right now!” he squealed, through bugged eyes and clenched teeth.) Even I recognized a fair amount of themes from the original films. But the new ones worked so well in context that I had to consult with my husband to make sure they were, in fact, new.

Rey’s theme, beautifully played by Gloria Cheng, stuck in my head for days. And once I knew which themes were new and which were throwbacks, I better appreciated how they worked together. There was a lot of ingenious counterpoint happening between them. And the interplay of these themes allowed for a fun guessing game: based on the musical material, what might be happening in the plot?

Due to the top-secret nature of the film, the footage wasn’t shown on a large screen behind us, like it usually is. One of my friends, a harp player, was able to see Williams’ personal monitor from where she was sitting. She was also privy to a few hushed exchanges between JJ Abrams and Williams.

On one such occasion, she deduced the death of a major character. After the session, she confided: “I don’t know if I was supposed to see that. Seems like a big spoiler!” It’s a good thing she, like me, is not a die-hard fan. That’s why she told me. (And no — neither of us ruined it for anyone.)

JJ Abrams and Williams’ relationship was something to behold. JJ thanked Williams many times over in the most sincere, touching, and gracious ways. Although the recording studio was clearly Williams’ kingdom, he was nothing if not genteel and humble sovereign. He shushed applause each time he received it — which was often. Daily, in fact. Each day felt as though he were receiving both a lifetime achievement award and a grateful, reverent embrace from the room. I couldn’t help but wonder what it must be like for him to know his music has touched billions of people in profound ways; sustained an industry; and inspired countless artists, likely well beyond his own lifetime. To know — at 83 — that he was making film music history in the here-and-now. It was a privilege to observe.

He seemed truly humbled by the scope of his own life’s work. All this reminded me of one of my favorite quotations (from Nabokov’s autobiography, “Speak, Memory”):

It is certainly not then—not in dreams—but when one is wide awake, in moments of robust joy and achievement, on the highest terrace of consciousness, that mortality has a chance to peer beyond its own limits, from the mast, from the past and its castle tower. And although nothing much can be seen through the mist, there is somehow the blissful feeling that one is looking in the right direction.

Williams referred to every ten-minute break as “intermission,” and to his players as “people.” (“Alright people; we’ll take intermission now.”) And he thanked all of his people for the stellar jobs they did. This included Bill Ross for conducting when Williams couldn’t. It also included Mark Graham and his team for music prep. Our friend Paul, giddy in his own introverted way, was part of this orchestration team. He shared that orchestrating for Williams involved nothing but transcribing clear intentions. Williams was exacting in what he wanted from each specific player. There was no guesswork required; no lines to be colored in.

I myself summoned the courage to thank JJ Abrams for two things. One, for his advocacy for scoring in LA; and two, for inadvertently introducing me to my husband because of it. When I shared that Philip and I met while scoring his show “Revolution,” JJ said I’d “made his day.” That made me laugh, seeing as the day in question was the final day of scoring “The Force Awakens.” What a mensch.

I lacked the courage, though, to get my photo taken with John Williams. Kevin wasn’t so sheepish.

kevin with the maestro on the last day of scoring

Kevin and I missed two sessions. Sadly, one of them was on October 12th — when they recorded the main title and end credits. With none other than Gustavo Dudamel as surprise conductor. Even I did a headdesk when I heard that news. Happily, the reason we weren’t there was because our Yosemite wedding was the day before. (Kevin was the officiant.) Luckily for us, we were there when they re-recorded the main title and end credits later on.

The only thing worth missing Dudamel conducting a star wars session. (Kevin officiated.)

And we missed a session in June because it conflicted with a Salastina performance. That, too, fell under the category of “worth it.” Same went for the cast & crew screening, which conflicted with a rehearsal of our Chamber Messiah. Thankfully, my recent husband did not divorce me over this transgression.

We saw the movie in the theater shortly after it came out. I cannot tell you how tickled I was to be able to hum along to themes that were unknown to everyone else in the theater.

Just don’t ask me for a plot summary.