Sounds Promising

/This weekend's concerts include the first performances by a Salastina Young Artist Ensemble. Sounds Promising has been several years in the making. We developed its structure and purpose through careful consideration of our own experiences -- as students, young professionals, working musicians, and teachers.

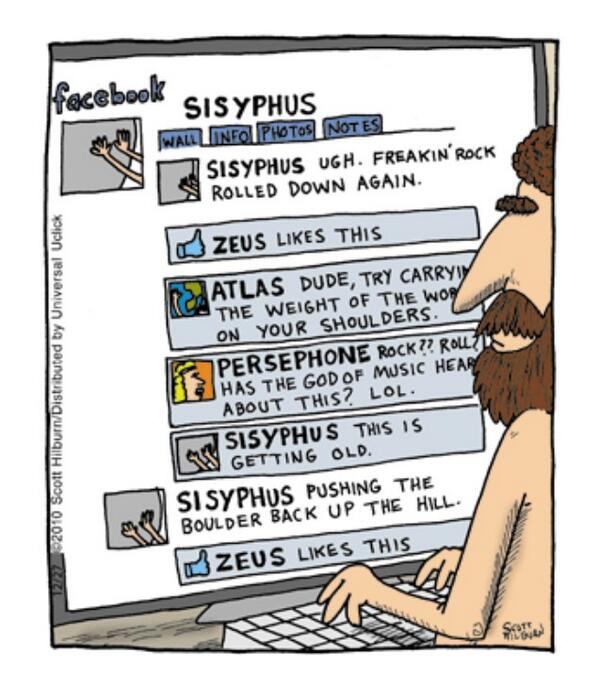

A Sisyphean Task

For student and professional musicians alike, the musical work is never done. We can always improve. We can always strengthen our technique, communicate more effectively, and perform more compellingly. We can always -- well -- sound better.

Not unlike opening a violin case every day.

When students are young, talented, and hard-working, the pressure is on all the more. Technically and musically, the most must be made of these formative years. It's as if there's not a moment to lose.

There is so much that's right with this approach. But there's a downside to the relentless pursuit of improvement, too. The resulting myopia leaves little time or space to consider much of anything else. When you're zooming in on, say, string crossings and Paganini caprices, it's hard to zoom out to crucial, bigger questions.

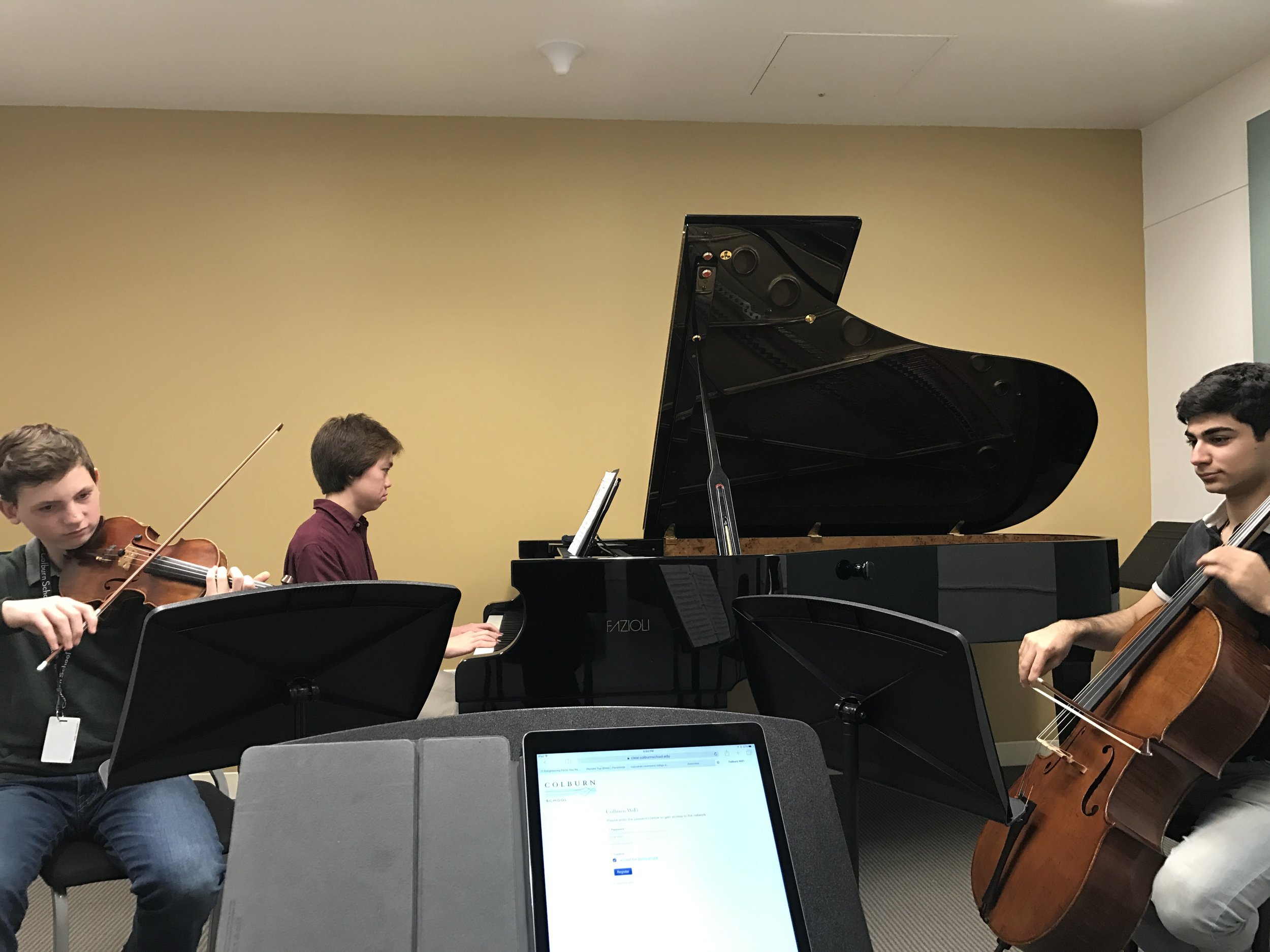

In the trenches with my honors piano trio at colburn. (This gifted and precocious group is also participating in sounds promising.)

Teachers' lesson slots are full enough with the sheerly musical tasks at hand. I don't fault any teacher -- myself included -- for devoting precious lesson time to musical progress alone. All the same, here are some questions I would hope enter the minds of music students -- one way or another:

Why do I really want to be a musician? Why is music important to me? Why is it important to other people?

What's it like to be a professional musician? What are my professional options? What is changing in society's musical landscape?

Why do so many musicians become jaded? How can I stay reasonably fresh, inspired, and fulfilled?

What strengths and interests do I have that are unique? What could those mean for my personal contributions to the field?

How do I feel about the prospect of taking dozens of auditions? How do I feel about the prospect of facing more rejection than success?

How do I quantify and define success? Is my definition of success something I realistically think I can achieve?

How do I feel about the prospect of spending nights and weekends away from my family and friends?

How do I feel about the prospect of having no regularity to my schedule or income? How important is lifestyle to me?

The above can be distilled into three fundamental questions:

What am I (and am I not) willing to suffer through in order to be a musician?

What's the point of making music?

What do I, uniquely, have to give?

In one's teenage years, the urgent need to improve and healthy, all-consuming passion leave little room for such questions. In my mind, this is a shame. This is the seminal developmental moment in which they most need to be asked.

Avoiding these questions makes it too easy for improvement to become self-involved. Don't get me wrong: the ego, ambition, and intrinsic motivation are crucial to artistic growth. But self-betterment for its own sake can just as easily miss the point.

Exhibit A: when I was in high school, I was consumed with worry about whether or not I'd be a "good enough" violinist. Yet I had no concept of what that question was really asking. "Good enough" for what? To earn a living and get a job? No, that wasn't it. The reality of such a prospect was too remote to trouble me. My concern was more ego-centric, more adolescent, and more abstract. I feared I was consigning myself to a future of perpetual self-loathing and frustration. I was worried I wouldn't be good enough to satisfy myself, and my own standards.

Sigh. I wish I had a time machine. I would tenderly pat my own angsty head, and say:

"Shut up, you. This isn't about what you want from the world; it's about what the world wants from you. Of course you'll never be good enough. That's what you're signing up for. Yes, we can handle the proverbial carrot always being a maddening distance from our nose. You know we love -- and live for -- that struggle. Isn't that the point of being alive? So relax. Practice smarter, not more. Don't pretend you don't know what I mean. And ask me some better questions."

Oddly Medieval Expectations

Few other professions today ask so much of teenagers. Dance and athletics are the only other fields that demand the same level of commitment from such a young age. But unlike music, they don't generally lead to careers that last a lifetime.

Led solely by their love of playing, passionate music students make long-term life decisions at incredibly tender ages. That's a beautiful thing to behold. But it can also be hard to watch. We music teachers bear no small amount of responsibility for guiding students through the process.

More often than not, students make these decisions naïvely. They can be woefully uninformed about disappointing future realities. After a considerable investment of time, money, and emotional energy, many throw in the towel. While changing direction can be healthy and necessary, I have to wonder what good could come of students having a clearer picture of the profession -- not just the craft -- before they commit to it.

To rationalize this with "everyone finds their own path," or "no life experiences are a waste," feels both disingenuous and reckless. It feels like a way to validate my own existence as a music teacher through platitudes.

Work, Job, Career

When I was a senior in college, I won a position in the New Haven Symphony. While I was proud to have my first job in a professional orchestra, I found the experience quite jarring.

Many of the musicians commuted from Boston, New York City, Hartford, and even Philadelphia. The pay scale was hardly commensurate with a commute of that distance. By contrast, rehearsals and performances were across the street from my dorm room. It took me zero effort to attend. While I felt sobered by others' commute, I am embarrassed to admit that I never once thought my life could look like that. (Flash forward three years to 2-hour commutes to the Pacific Symphony. At least I got a best friend out of the carpool.)

More sobering still: the attitudes of the musicians in the orchestra. The enthusiasm and collegiality of youth orchestra was nowhere to be found. I was shocked and dismayed to hear wind players criticizing the conductor during rehearsals. If I could hear their venom, I knew he could, too. It was depressing. Had the Ghost of Musician Future come to tell me that this work environment was my fate, I may well have changed course.

Happily, there's no such thing as ghosts. And I was too inexperienced to know that these phenomena were not unique to this orchestra. Besides: I had my sights set on chamber music, having conceived of starting a series two years earlier.

Shielded by a protective naïveté, I merrily continued my studies and my career track with the youthful confidence that things would work out. The disillusionment did not register with me as, perhaps, it could have.

I wasn't wrong to move through that first professional experience relatively unphased. Being green isn't all bad; it's important. In fact, idealism is something I hope to nurture in my students. But meaningful, useful idealism relies on insight, curiosity, and a reasonable dose of pragmatism. That's quite a different thing from naïveté.

I wish I'd had a clearer sense of something my husband and I now talk about often: the distinction between an artist's job, career, and work. To illustrate, I'll use myself as an example.

How my annual income has broken down over the past two years.

Studio and orchestral work is my job. It pays the bills, is consistent, and allows me to enjoy a respectable quality of life. Teaching and chamber music are my life's work. Their sum total, however, comprises less than a quarter of my income. In this way, my job supports my ability to do my work as an artist. My career? That would be both pie charts -- plus those behind and in front of them.

There's the obvious question of what I would want these pies to look like. Generally speaking, I'm working towards the growth of those little orange and green slivers. And I'm certainly happier this year than I was last year because of it. But as long as I'm doing enough of my work to fulfill and energize me, my job is supporting my livelihood, and the two are working in tandem to support my career as a whole, I really can't complain.

Our Program

I wish I'd had an inkling of these ideas when I was a student. They seemed elusive, and strangely irrelevant at the time -- a time when all that mattered to me was getting better. But what did success really mean for, and to, me?

I wish I'd had the opportunity to think about things in this way. I wish I'd had experiences that showed me, and got me thinking creatively about, what my professional future could hold. Above all else, I wish I'd had the opportunity to get my hands dirty with what appealed to me most: playing and presenting chamber music.

Sounds Promising is, in large part, about providing these kinds of opportunities. This is achieved through values-based action, guided collaboration with others, and close, focused access to professional musicians. You can read more about the specifics of the program here.

There are no straight lines to a dream career in music. Through Sounds Promising, we hope to equip young musicians with the tools and experiences to more effectively navigate what will inevitably be a hazy circuit of unknowns.